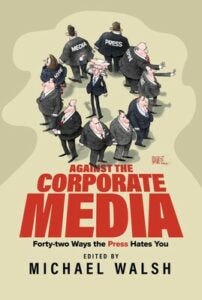

An excerpt from Against the Corporate Media, coming Sept. 10 from Bombardier Books. "Nixon and the Weaponization of Media Hate," by Monica Crowley.

The origins of the press’s Nixon hatred go back to his earliest political days. From the moment he first ran for Congress in 1946, he was a staunch anti-communist, committed to fighting Marxists both abroad—and at home. And rather than cast his lot safely with the Establishment, he stood for and with the American people—whom he later famously called the Great Silent Majority—and championed them and their interests ahead of those of permanent Washington. He was America First long before Donald Trump came down the escalator in Trump Tower.

This forever earned him the deep, abiding enmity of anti-American agitators, communist sympathizers, and garden-variety leftists everywhere, including in the press, among the Democrats, and in what we now know as the Deep State.

That enmity was evident right from the start of his political career. In 1948, freshman Congressman Nixon was a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee, investigating communist infiltration in the U.S. government. The Committee became aware of Whittaker Chambers, a former communist functionary who left the party completely disillusioned and later went on to be a senior editor at Time magazine. In his blockbuster testimony to the committee, Chambers identified the depth of communist infiltration, pointing directly to senior members of the government, including Alger Hiss, a former State Department official and prominent Democratic functionary involved in the creation of the United Nations.

You really can't hate them enough.

Hiss was a darling of the press with the perfect establishment pedigree: A graduate of Harvard Law School, he served as secretary to Supreme Court Justice Oliver Holmes, was a top adviser to President Roosevelt at the Yalta Conference, and was a major force behind the creation of the United Nations. Tall and handsome, Hiss glided through the corridors of power with ease. The only problem was that he was a communist who had passed secrets to the Kremlin, and Nixon proved it. Hiss was eventually convicted of perjury, and Nixon was catapulted into the national political limelight. That sensational event set Nixon on a collision course with the press, many of whom had communist sympathies and hated that he had exposed one of their own. Nixon himself identified the Hiss case as the origin story of his war with the press.

Nixon ran for and won a seat in the U.S. Senate from California in 1950, in part by insinuating that his opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas, was a communist sympathizer. One of his campaign’s leaflets, comparing her record to that of a notorious communist party-line congressman from New York, was printed on pink paper, and later in the campaign, Nixon suggested that she was a “pink right down to her underwear.”

These tactics were condemned as below-the-belt and set many in the press off on career-long jihads against Nixon, including Herblock, The Washington Post’s star political cartoonist, who first drew Nixon as a sewer rat after the Senate race—and never stopped vilifying him. But the tactics worked: Nixon won that race and further cemented his anti-communist credentials.

In addition to the Hiss case, another event accelerated his sour relationship with the press. In late 1952, as he headed into the general election as Dwight Eisenhower’s choice for vice president, he was hit with allegations that he had misappropriated campaign funds. Reporters smelled blood. Sensing that his place on the ticket might be in jeopardy, Nixon delivered a national primetime address—known as the Checkers speech—in which he laid out the facts, attacked the smear merchants behind the story, and asked the audience to let the Republican National Committee know if he should stay on the ticket.

The public response was overwhelmingly in support, Nixon became vice president, and the press once again was proven wrong. Prior to the speech, Nixon and some in the press still courted each other, but following the address, they turned on each other. When some reporters were late for a campaign bus, Nixon reportedly snapped, “F-ck ’em, we don’t need ’em.” His press secretary, Jim Bassett, summed it up: “By the end of the ’52 campaign, he had utterly no use for the press.”

Nixon handed Vietnam to the communists, supported the progressive cause by giving the vote to eighteen year old war protestors. Gave the Chinese a proper validation, leading to them becoming the nuclear threat they are today. A whole lot of aid and comfort from a man who hated communism.

Chew them up and spit them out Monica